From ageing to longevity: harnessing innovation to tackle the cost of not caring

NSSN Board Member Dr Abby Bloom is a global authority on technology in health, ageing and longevity. In this excerpt from her latest book The Cost of Not Caring: Working while Caring in the Era of Longevity, she lays bare the unfolding ageing crisis and offers practical, innovative and low-cost solutions to ease the burden of balancing work and care.

Ageing is a very hot topic today. Why? We are well and truly in the 20+ year era of longevity, and utterly unprepared for our longevity economy.

Dr Abby Bloom. Credit: Supplied

The longevity economy (the sum of all the goods, services, capital investment and – sometimes – unpaid care) - is vast: the The Treasury projects it to reach $110 billion next year.

Ageing – and longevity – demand urgent responses

By 2030 Australia and many other nations will reach a milestone: more residents 65 and older than 18 and younger.

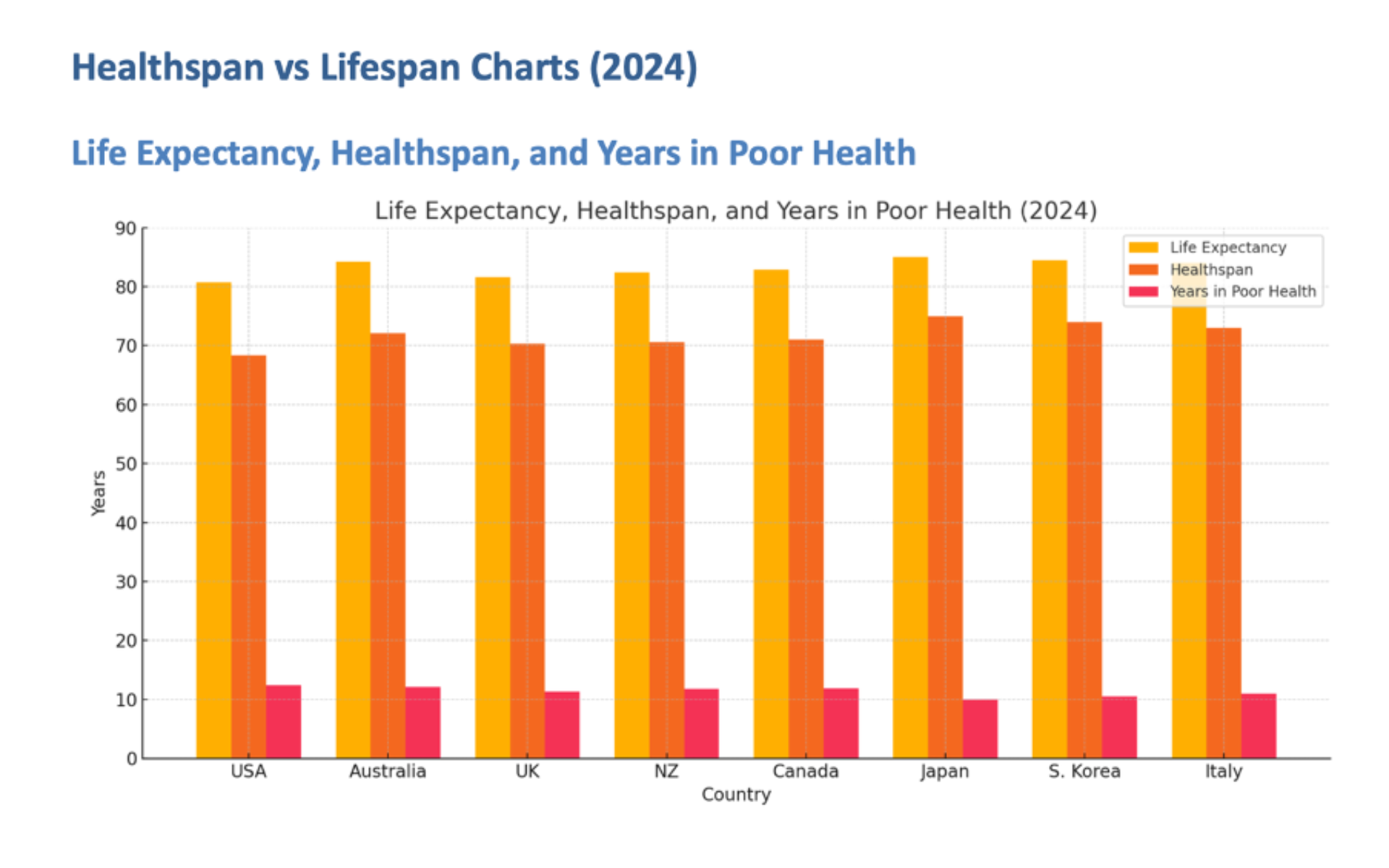

While the average lifespan has increased, the ‘carespan’ hasn’t budged and sits at 8-9 years on average.

Carespan is the period of life in which older adults will need support and care to age with dignity and independence, ideally in their own homes.

The challenge isn’t ageing, it’s responding to longevity, the fact that people need support and care, including funding, people and systems to support their living, their longer lifespans – longevity.

Credit: OECD Health at a Glance 2023; WHO Global Health Estimates; peer-reviewed summary data from The Australian Population Research Institute 2024.

A crisis of our own making

Australia’s support for longevity/ageing is no longer fit for purpose.

The structure may have been adequate in an era when men worked and women stayed home and cared, when average family size was 4 children so there were plenty of adult children to care for two or three generations – children, parents, partners.

Today it is an incoherent combination of state, federal, and charitable organisations leaving older adults and their families falling though the gaps.

Funding is insufficient and incoherently distributed among numerous different organisations and programs.

This impenetrable system, and gaps, have costly consequences.

The costs of not caring – an almost total lack of support for unpaid family carers trying to work while caring - are many and include:

· The out-of-pocket payments families must make while they wait months and years long waiting lists for support and care. Sometimes they are forced to dig into their savings and superannuation to cover costs. The in-kind costs in the growing hours and value of unpaid care shifted to families.

The cost of not caring: unpaid carers forced to drain savings, sacrifice jobs, and carry crushing stress — while employers lose skilled workers. Credit: AdobeStock

· Carers’ psychological stress with family the release valve for a dysfunctional system, plugging the supply and funding of care; resigning from jobs they should be able to keep; reducing their hours; refusing promotions to keep flexibility in their work lives; and the health care costs of unpaid carers who are mentally and physically exhausted.

· Employers losing valuable employees when care responsibilities make it impossible to hold down a job – and the productivity-sapping costs of recruiting and training replacement staff.

What’s innovation got to do with it?

There is unlikely to be in the short- to medium-term enough government funding, or available paid carers, for the support and care Australia’s older adults need to age at home – which 90 % plan to do.

Their adult children working while caring can’t juggle it all. They’re smashed.

That’s why innovation is an essential circuit breaker – and especially innovation that combines sensors, software and AI.

We’re seeing a flood of AgeTech innovation and adoption elsewhere – but not in Australia.

Sadly, our government does not subsidise digital technology: it is not on the quaintly named “Assistive Technology” list of subsidised support tools (handrails are one example of what is classified and approved “assistive technology”).

Innovation FOR, not just USED BY, older Adults

A common misapprehension about older adults is that older people don’t use technology, so innovation is pointless.

Older adults do use tech. But the question is wrong.

The correct question is: How can innovation be used for the benefit of older adults, not necessarily by them?

Bright shiny things or process innovation?

Both are needed. We love humanoid robots, and they are slowly finding their place supporting older adults with lots more to come.

But there is so much more device technology available now, from mini-exoskeletons (Biomotum), to real-time captioning eyeglasses for people who have cognition or hearing issues (Xander).

There is support for people with dementia and their carers, like Memory Lane Games, literally a game app which has garnered 2.9 million views since highlighted recently by Google Play; to software converting an existing TV into an interactive device curated for seniors’ connectivity and care.

Process innovation, including AI, can introduce huge administrative cost savings in both residential and home care.

It is sorely needed to increase productivity in the aged care sector, and to simplify the lives of families caring for older parents.

Australia’s ageing, challenge, our longevity economy, is an opportunity crying out for innovation – for older adults, their families, governments, and the organisations who rise to the challenge of innovation. It’s a unique opportunity for a win-win-win-win.

Dr Bloom is also a non-executive director; an Adjunct Professor at UTS Business School; and a co-founder of Prime Life Partners. She has extensive unpaid care experience: her mother lived with dignity and joy in her own home to 109. She will moderate the panel discussion on sensor care devices at the NSSN’s 4th Ageing Forum.

The Cost of Not Caring: Working while Caring in the Era of Longevity is published by The Book Adviser.